by

Dr Stephen J Nash | Nov 21, 2012

Recently, we argued that there was no bond crash on the horizon. This article substantiates our recent analysis by looking at recent Fed commentary and IMF warnings in regard to growth expectations, to highlight the case that a bond crash is some way off.

The market had become somewhat over-optimistic on growth, in the wake of a long and drawn out announcement of QE3. While earnings expectations had lost touch with reality, those expectations have recently come crashing down as a result of the following series of events and announcements:

- Earnings were worse than the elevated expectations had suggested

- Expectations on key equities, like Apple, had become over exuberant

- US elections re-focussed the market on the possibility of a fiscal contraction in 2013

- European growth has continued to falter

Hence, the idea of a growth breakout, and the consequent bond crash, as expected by some, especially those pushing high risk asset allocations to clients, have proven incorrect. In this piece, recent Fed commentary is considered, along with recent IMF warnings on growth. Both tell a very consistent story; do not be complacent on growth. Some recent movements in bond and equity indices are also reviewed, with a view to ascertaining what the markets are beginning to price in.

Fed commentary

While the US Federal Reserve (the Fed) has two major goals, price stability and full employment, Williams, from the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) provides a good summary of the current situation below,

Let’s start by considering the goals Congress has assigned us: maximum employment and price stability. What exactly do these concepts mean? Let’s start with maximum employment. Now, maximum employment does not mean a situation in which everybody is working. Instead, economists think of it as the level of employment that the economy can sustain over time without inflation rising too high. Economists fiercely debate what the unemployment rate would be under maximum employment. Typical estimates are between 5 and 6 percent. Thus, by almost any credible measure, the current 7.9 percent rate is much higher than we would get at maximum employment.

What about price stability then? Fed policymakers have specified that a 2 percent inflation rate is most consistent with healthy economic growth and our mandate from Congress. So where are we? Inflation has averaged only 1.7 percent over the past year, below this 2 percent target (“The Role of Monetary Policy in Bolstering Economic Growth”, Presentation to the University of San Francisco, Center for the Pacific Rim, By John C. Williams, President and CEO, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, For delivery on November 14, 2012).

In other words, officials at the Fed are indicating that they are undershooting on both goals; inflation is too low and employment is too low. While the economy might be close to the point where the Fed might tighten, the communications strategy from the Fed is much more advanced from where it was in 1993, just before the crash, as Yellen recently observed,

To fully appreciate the recent revolution in central bank communication and its implications for current policy, it is useful to recall that for decades, the conventional wisdom was that secrecy about the central bank’s goals and actions actually makes monetary policy more effective. In 1977, when I started my first job at the Federal Reserve Board as a staff economist in the Division of International Finance, it was an article of faith in central banking that secrecy about monetary policy decisions was the best policy: Central banks, as a rule, did not discuss these decisions, let alone their future policy intentions. While the Federal Reserve is required by the Congress to promote stable prices and maximum employment, Federal Reserve officials at that time avoided discussing how policy would be used to pursue both sides of this mandate. Indeed, mere mention of the employment side of the mandate, even by the mid-1990s, was described in a New York Times article as the equivalent of “sticking needles in the eyes of central bankers” (“Revolution and Evolution in Central Bank Communications” Remarks by Janet L. Yellen, Vice Chair, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, at Haas School of Business, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, California, November 13, 2012).

Now the Fed is keen to use better communication to increase the effectiveness of policy, so that if we did get close to the need for a tightening, then the Fed would be much more open to the market than it was in 1993, just before the bond crash of 1994.

IMF analysis

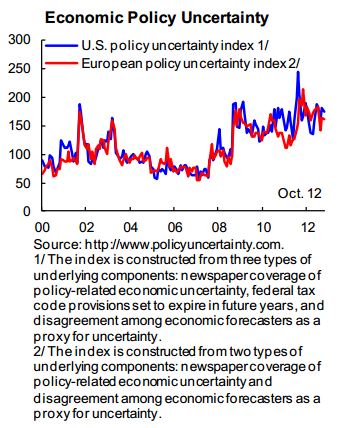

Recently, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has issued a document that illustrates the many risks that face advanced economies. This is not just a routine warning; it is a warning to the members of the IMF that global growth is precarious for many important reasons. In particular, the IMF estimates that most countries will be experiencing slow growth as a result of further European stress, as the below figure indicates. It looks like the question is not whether Europe will impact global growth more than it already has, but how much more. Importantly, the current level of policy uncertainty is not helping the current situation, as investment is being held up, until some clarity on the direction of the economy is provided (see Figure 1).

Source: IMF, Group of 20, Global Risk Analysis, Annex to Umbrella Report for G-20 Mutual Assessment Process, Prepared by Staff of the IMF, p.4

Figure 1

In addition, the IMF note the following:

- While growth is recovering, the recovery is “fitful” with variations in member countries apparent

- Even though global financial conditions have stabilised, financial stress has re-emerged

- European crisis management activities are proceeding, yet the dampening impact of fiscal austerity on growth, is apparent

- One of the areas of acute concern to the IMF is the deleveraging by Euro area banks, which is amplifying the fiscal austerity measure in the system

- Peripheral European governments are experiencing reform fatigue, and this may threaten current reform procedures

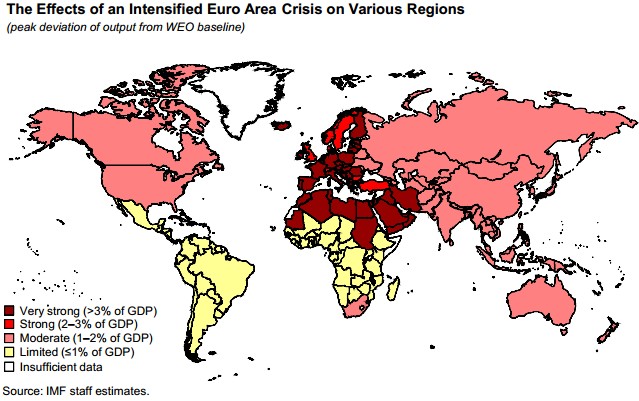

In terms of the risks to growth, the IMF see that world economic recovery remains highly vulnerable, with Europe remaining in a “danger Zone” (IMF, Group of 20, Global Risk Analysis, Annex to Umbrella Report for G-20 Mutual Assessment Process, Prepared by Staff of the IMF, p.5). While one might have thought that the European crisis was already over, the IMF are actively looking at the prospect of what an intensified Euro Crisis might mean for the various regions of the world. As the Figure 2 below indicates, the impact of further problems in Europe will be widespread, including most of Asia, Australia, and the United States.

Source: IMF, Group of 20, Global Risk Analysis, Annex to Umbrella Report for G-20 Mutual Assessment Process, Prepared by Staff of the IMF, p.7

Figure 2:

On top of all this, there are two other major problems for global growth:

- A contraction in the US, due to the need to reign in debt, is also seen as very real threat to global growth

- Geopolitical tensions in the Middle East, which may lead to another spike in oil prices, which may dampen global growth

Bond market catching up, again...

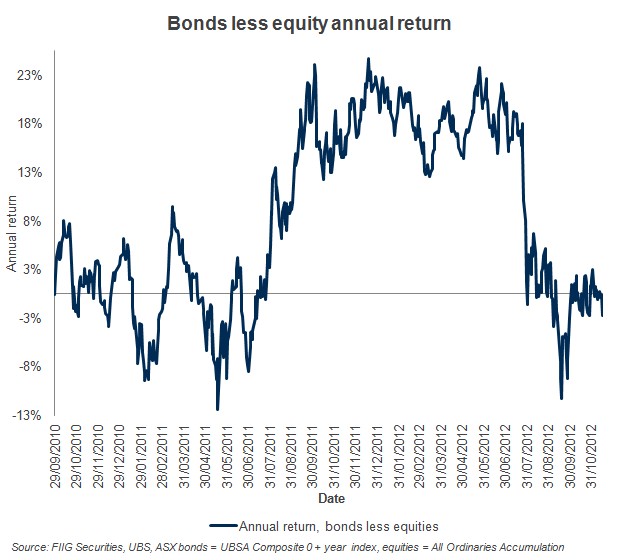

The above warnings on growth tend to have been ignored for most of this year, although that is changing of late. As expectations of QE3 proceeded, the expectations for equities lifted and that led bonds to recently underperform equities on a rolling annual basis. These hopes led equity returns up in July, and led to bonds to underperform equities for the last few months. However, as the expectations for equity market proved unfounded, the rolling annual return for equities has waned of late. Warnings about growth, as listed above, are set to moderate earnings even more and bonds look set to outperform equities once again, as indicated in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3

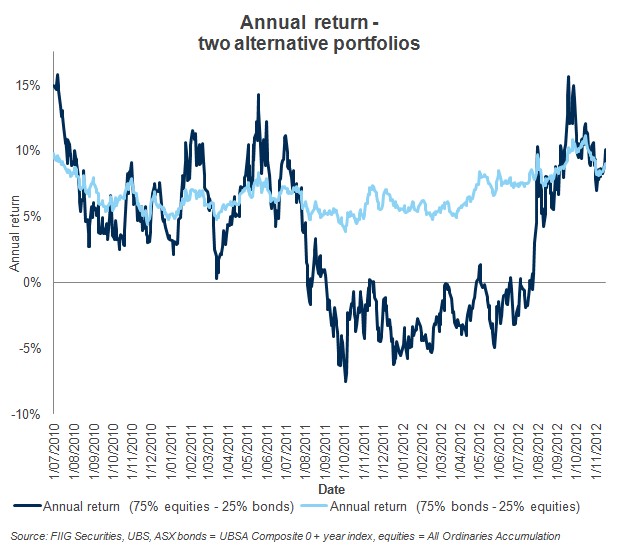

While return is always an important concern, the main criteria for investors should be risk, and the possibility of much smother returns is easy to obtain, by simply flipping the typical “balanced” asset allocation on its head, so instead of allocating 75% to equities and 25% to bonds, one should allocate 75% to bonds and 25% to equities, as Figure 4 shows.

Figure 4

Notice how the bond biased portfolio has a high and constant return, whereas the equity biased portfolio has a very volatile ride, slipping into negative annual return quite easily, and for an extended period.

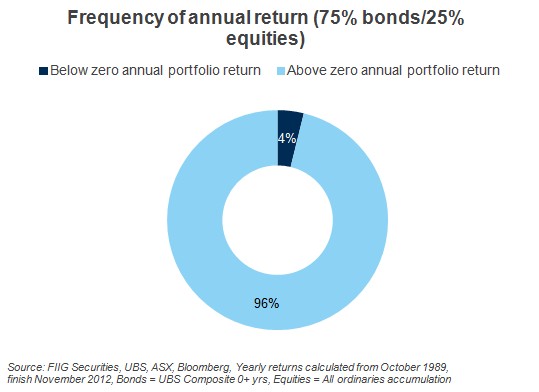

The relative certainty of such a bond weighting is illustrated in the Figure 5, where the possibility of below zero portfolio return with 75% bonds and 25% equities is very low; under 5%. In contrast, the possibility of a negative annual return with a 75% allocation to equities and 25% bonds, is five times this; around 20%.

Figure 5

Conclusion

Bond crash talk is, in our view, highly premature. Such talk appears to be driven by vested interests by those who want to sell products with not only high return, but high risk, and the higher fees attached to such risk. Also, such discussion fails to appreciate what the Fed has now done in terms of improving communication with the bond market. In other words, the discussion of a “bond crash” is not only alarmist, it is unhelpful to those who need to focus on asset allocation. Such alarmist discussion is all the more misleading in the context of most official commentary, which is very conservative on growth, and which continues to highlight the risk that growth will be lower for longer. While the Fed thinks employment is too low, it also hastens to add that inflation is too low.

This is hardly the stuff of a bond crash.

If anything, this type of commentary is much more supportive of weaker growth and better returns in bonds, than equities. While recent IMF warnings support the case made by the Fed, the recent annual return data in Australia points to bonds taking back the lead, in terms of annual return. Despite the ongoing tussle, between bonds and equities, in terms of annual return, the greater certainty of a bond biased portfolio seems fairly clear. In this environment, it should be possible for Australian government ten year bonds to make more fresh lows in yield, as part of this ongoing narrative; of low growth, low inflation, and a local equity market struggling to come to terms with such a situation. Bonds are not only here to stay, they will remain able to provide relative certainty for many years to come, and those who are warning of a “bond crash” are generally of little assistance in setting overall portfolio asset allocation.