by

Justin McCarthy | Oct 24, 2012

Last week’s article “Low growth is here to stay – Ignore the ‘bond bubble’ myth” by Dr. Stephen J Nash prompted lots of questions around so called “bond bubbles”. In response we have answered a number of the frequently asked questions and address in greater detail some of the common misconceptions that exist around “bond bubbles”.

What do the terms “bubble” and “bond bubble” mean?

In financial markets the term bubble typically refers to a market that is over-valued and the inference is that the bubble is likely to burst with a rapid loss in market value. It is also an indication that the price is out of sync with the fundamentals or not sustainable over the medium to long term.

“Bond bubble” typically refers to the rise in value of fixed rate bonds as interest rates fall. Technically speaking it is duration risk. In most cases this is quoted in reference to Government bonds and most often US Treasuries, being long dated fixed rate securities. However, we would argue the rise in price of fixed rate bonds (particularly government bonds including US Treasuries and Australian Government Bonds) is in most cases not unrelated to fundamentals or out of sync with the broader market. Interest rates are falling for good reasons, many of which were set out in Dr Nash’s article from last week.

How do they differ?

It is the difference between the typical bubble and so called “bond bubble” which set them apart. These include the following:

- Unless the issuer (e.g. Australian Government) goes broke, which is extremely unlikely, you will still receive your $100 face value at maturity and known fixed interest payments every six months if you hold to maturity. Whereas a typical bubble such as the tech bubble in equities will often see a massive fall in value of 50% or more in a very short period. So the worst you can do from bonds is to get your interest and face value back. This same obligation is not relevant when an investor puts money into a fund or buys an equity.

- “Bond bubbles” are driven by interest rates and future interest rate expectations. It is rare for a massive change in interest rate expectations in a short period and as such the price of fixed rate bonds don’t typically fall significantly in just a day or two. Rather, the price may fall over weeks or months as economic news and interest rate views change, providing time for bond investors to exit if they wish. On the other hand, equity bubbles may “burst” in hours or days.

- “Bond bubbles” only refer to fixed rate bonds. Floating rate notes and inflation linked bonds do not move to the same extent on interest rate expectations but very tight credit spreads or inflation expectations can result in some bubble like behaviour. Interestingly, it is these types of bonds where there can be a disconnect between the fundamentals and market prices but again the downside is limited with interest and principal still a legal obligation.

- As long as investors remain comfortable with the credit risk of the issuer, investors do not panic out of their holdings like they do in other “bubbles” meaning there isn’t a self perpetuating panic (such as the tech-stock bubble or even housing prices bubbles). Further, “bond bubbles” are less susceptible to leverage driven margin selling (but this is still possible). In the end the fundamentals of bond prices and interest rate expectations keep a reality check on the extent of any sell-off.

It is important to note that direct ownership of bonds enables closer monitoring and management of so called “bond bubbles”. Where investors usually get caught by “bond bubbles” is in managed funds and fixed income/bond funds when the manager decides to sell out at the wrong time/gets their asset allocation decisions and timing wrong.

What are the risks of a bond bubble?

Unlike normal bubbles where the price of the asset can fall in theory to zero, the main risk of a bond bubble for investors is that they have purchased the bond at a large premium above the $100 par/face value and this price falls. If an investor needs to liquidate their position prior to maturity this may involve a capital loss.

However, as emphasised above, the worst case scenario on a hold to maturity basis (assuming the issuer does not go broke) is that the investor gets all their scheduled (fixed) interest payments and $100 face value back at maturity. Meaning the biggest risk is a relatively small fall in market value, say $5 to $20 depending on the bond.

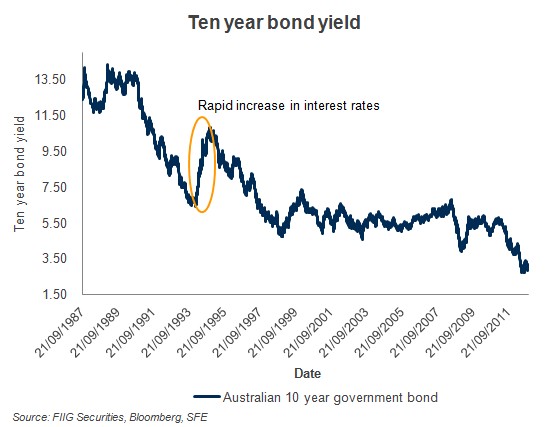

Generally speaking a decline in fixed rate bonds will be when the economy is booming (and interest rates are rising). In such an environment other asset classes, particularly equities and property are improving, which enables a smoother performance of the average diversified investment portfolio. But this is not always the case as Figure 1 below demonstrates when interest rates rocketed in 1994.

Figure 1

Are corporate bonds susceptible to “bond bubbles”?

As discussed above, the main feature of bond bubbles are interest rates and how they affect fixed rate bonds. As such, long dated fixed rate corporate bonds can exhibit much of the same movement seen in government bonds. However, there is an additional factor that affects corporate bonds and that is the credit spread or market’s assessment of credit worthiness.

While it isn’t always the case, the text book tells us that generally interest rates rise when the economy is growing (or in boom cycle) which is bad for fixed rate bonds , remembering the inverse relationship between interest rates and fixed rate bond prices. However, in a “booming” economy, credit spreads are typically low /falling and this is positive for bond prices. As such, the negative impact of rising interest rates is offset somewhat by falling credit spreads.

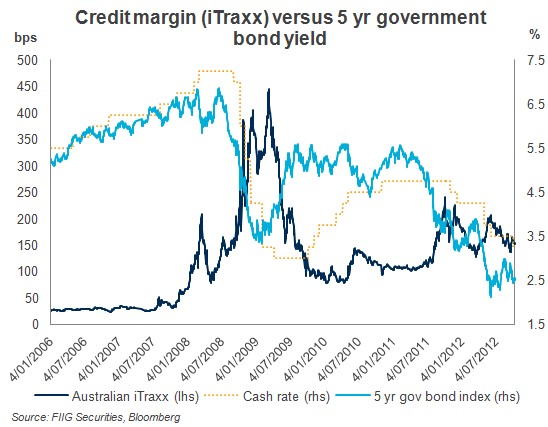

Figure 2 below demonstrates the inverse relationship between credit spreads (as depicted by the Australian iTraxx, dark blue line) and interest rates (the RBA official cash rate, yellow dotted line and five year government bond yield, light blue line).

Figure 2

Prices of floating rate notes (FRNs) are predominately driven by credit spreads and again in broad terms will outperform in a boom cycle and underperform in a bust cycle. The direction of performance of FRNs is often in line with equities but the extent and volatility is significantly less than that seen for equities.

Do FRNs and inflation linked bonds (ILBs) alleviate the risks of “bond bubbles”?

In a nutshell, yes. While there can be pockets of risk from unrealistically tight credit spreads or expected inflation , the main risk of “bond bubbles” are rising interest rates on fixed rate bonds. FRNs and ILBs do not have material price movements from rising interest rates. Rather, they tend to outperform in rising rate environments as credit spreads typically tighten and inflation expectations increase as growth accelerates.

Do bond funds have exposure to “bond bubbles”?

Depending on the fund, yes. Most bond or fixed income funds tend to have a large weighting to fixed rate bonds (or duration), especially government bonds.

Many funds or the fixed income allocation of funds are managed to a fixed income index such as the UBS Composite Bond Index which is heavily weighted to fixed rate bonds, mainly high quality Government and semi-Government bonds. The vast majority of Government bonds are only issued as fixed rate.

As such, a typical bond or balanced fund will manage to that index and will only change and re-balance to the small changes in that index. Further, a manager will want the liquidity and safety of Government bonds and hence is pushed towards fixed rate bonds. This is especially true of very large funds such as PIMCO that will move the market when they decide to change investment positions.

Bond funds are much less likely to have a large allocation to FRNs and/or ILBs. Moreover, the investment decisions and asset allocations of funds are typically very static meaning that if the market starts to turn, it is unlikely a fund manager will sell all of their fixed rate bonds or government bonds and move into FRNs, ILBs or even equities and other asset classes that outperform in rising rate environments. In the vast majority of cases they will retain the management of the fixed income portfolio allocation close to that of the underlying benchmark index.

Duration based fixed income products such as EFTs and indexed funds management has led to the fear of “bond bubbles”. Fund managers following an index need to match the average duration of the universe of bonds, so they are forever lengthening their portfolios to keep up with new issuance

For these reasons we often recommend direct ownership of fixed income rather than using fixed income managed funds (amongst other reasons such as loss of return from fees and risk of funds being frozen). If an investor wants duration or exposure to fixed rates, they can buy one government bond or better still a diversified portfolio of bonds with various maturities that provides flexibility to trade, exit or simply hold to maturity as required.

A fixed maturity bond will eventually pay you back, provided you are comfortable with the credit worthiness of the issuer. In contrast, investments that have no maturity (such as equities, property or a managed fund) need buyers for you to be able to get your money back.

What can I do if I have fixed rate bonds and believe interest rates will rise (or I am exposed to duration via a bond fund)?

First and foremost it is always difficult to time the markets but if an investor fears rising rates there are many courses of action:

- Reduce duration risk by selling down fixed rate bonds at the current very high market values and re-invest in FRNs or ILBs (or other asset classes)

- Hold to the bonds to maturity and continue to receive fixed interest payments and the full $100 face value on maturity

- If invested in bond funds, ascertain the exposure and strategy regarding fixed rate bonds/duration. If the manager is unlikely to change their allocations to fixed rates then it may be a good time to exit the bond fund and invest in direct fixed income, particularly FRNs or ILBs or even shorter dated fixed rate bonds

What are the effects of a change in interest rates on a fixed rate bond, particularly the market value and cashflow?

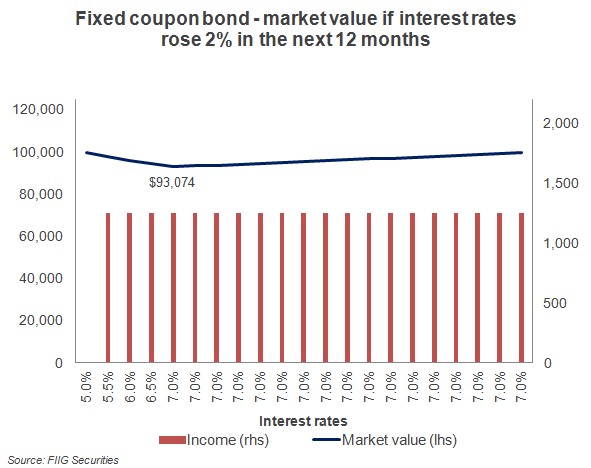

The following hypothetical example shows the impact on both market value and cashflow.

If you purchased a five year fixed rate bond paying 5% p.a. today for $100,000 and interest rates rose 2% over the next 12 months (at 0.5% a quarter), then remained the same until maturity, the market value of that bond would fall to a low of $93,075 in a year’s time before increasing in value over the remaining four years until maturity at which time you would receive your $100,000 back (i.e. “pull to par”). Over that time you would also receive $25,000 of coupons (see Figure 3).

Figure 3

For more information please call your local dealer.