by

Dr. Stephen Nash | Mar 13, 2013

Inflation can erupt from a variety of sources. With elevated levels of quantitative easing apparent in the developed world, the spectre of elevated inflation remains apparent, and should not be ignored. Tensions in the middle-east remain elevated, with some describing the situation, especially regarding Iran and the Syrian conflict, as bad as the Islamist revolution of 1979 where US hostages were held for 444 days. Conflict in the middle-east could easily escalate from here, given Israeli concerns both about the war in Syria and the emergent nuclear capability of Iran. Such conflict could then lead oil prices, and inflation, higher; possibly much higher. While the RBA has done an excellent job regarding the control of Australian inflation, some things remain outside the scope of the RBA to control meaning that risks remain and one should not be complacent on the issue of inflation, as all forms of saving will suffer with higher inflation.

More specifically, in the following note the main asset classes that are seen as providing insurance against inflation are considered, as follows:

- house prices

- gold

- commodities, and

- equities

With each of these asset classes, the typical argument for why that asset class provides insurance against inflation is considered. Consideration of the relation between annual Australian inflation and the asset class in question is then given, before assessing the rolling five year correlation between the asset class annual return and annual Australian inflation. We also consider the advantages and disadvantages of each asset class, from the perspective of how the asset class provides insurance against inflation.

By way of conclusion, we argue that relatively inexpensive forms of insurance against inflation exist in the form of inflation linked bonds, where a reliable hedge against inflation exists.

Throughout this article we refer to a “correlation”. Correlation measures the statistical relationship between two variables, where a strong positive correlation implies that two variables will move together, where a negative correlation implies that the two variables will move in opposite directions. In the charts that follow, a strong correlation and hence a good protection against inflation, would represent a figure higher than 20% on the rolling five year correlation measure. Correlation should not be used to imply causation, or that a movement in one variable causes a movement in another variable. Generally, we are looking for forms of insurance that provide reasonably positive correlations to Australian inflation as the higher the correlation the better the asset class provides insurance against inflation.

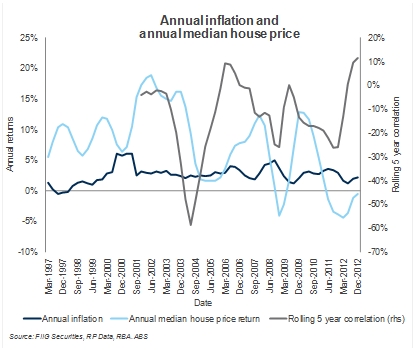

House prices

House prices are seen as a way to insure against inflation, as the cost of housing comprises one of the groups within the inflation calculation as created by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). However, house prices, like most perpetual income producing assets, tend to be impacted by expectations of future earnings. Readers should not need to be reminded of how volatile expectations of future earnings can be, and since house prices are more linked to these volatile expectations they have a low, and somewhat volatile correlation to inflation; hardly a reliable form of insurance against inflation, as shown in Figure 1 below. While generally positive, house prices are much more volatile than the annual rate of inflation, although the recent annual performance of house prices is somewhat lower than the late 1990’s. Given the success of the RBA in stabilizing inflation and lowering interest rates, the large increase in house prices was probably due to the decline in funding costs for housing, yet has also lead to quite a volatile history for house prices.

Figure 1

One can summarise the advantages and disadvantages of housing, as a form of insurance against inflation as follows:

Advantages

- Housing is an important aspect of some of components of the CPI

Disadvantages

- Housing has limited representation in the CPI, and other factors remain important for inflation at different times, and

- Correlation of returns to inflation remains poor

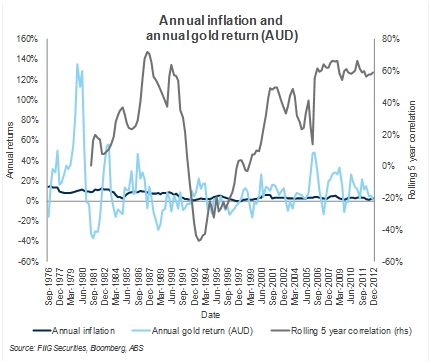

Gold

Gold is a commodity that is often seen as a way to insure against inflation, especially against a currency devaluation, as the supply of gold is largely fixed and is expected to stay largely fixed over the medium term. In the past, some currencies used conversion to gold as a way to stabilize the value of a currency. Main sources of demand are as follows, according to the World Gold Council, Gold Demand Trends 2012, issued February 2013:

- central bank purchases

- jewellery

- technology, and

- investment

These sources of demand have little to do with Australian inflation, and the interaction of demand with supply, as reflected through the gold price, has led to a very volatile history. The correlation to the Australian inflation rate is volatile, although a little better than the correlation between annual house price changes and annual inflation. These observations are indicated in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2

One can summarise the advantages and disadvantages of gold, as a form of insurance against inflation as follows:

Advantages

- Gold can represent insurance against a weak currency, and remains a stable source of value

Disadvantages

- Demand and supply for gold has very little causal relationship to the rate of Australian inflation, and

- Correlation of returns to inflation, whilst typically positive, remains poor

Commodities

Commodities are also seen as a way to insure against inflation, since inflation is comprised of items that are made from the basic commodities. Hence, if commodity prices rise, then the Australian rate of inflation should rise. In measuring the changes in commodity prices we have used a widely utilised benchmark; the Commodity Research Bureau, US Spot All Commodities index. This index measures the spot prices of around 22 commodities, such as copper, butter, cotton, and some metals. However, the Australian CPI is not exclusively tied to commodity prices, as it has many service related categories, so that the CPI reflects both labour cost as well as basic commodity prices. As Figure 3 shows, commodity prices in Australian dollars, are much more volatile than the Australian inflation rate, as the prices of commodities like other prices are impacted by those notoriously volatile expectations of future growth. However, the correlation is reasonable, especially since 2000, although quite volatile.

Figure 3

One can summarise the advantages and disadvantages of commodities, as a form of insurance against inflation as follows:

Advantages

- Commodities drive part of the Australian inflation rate

Disadvantages

- Australian inflation is driven by other forces, apart from commodities, and

- Correlation of returns to inflation remains poor

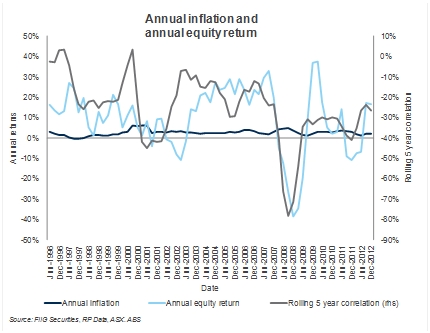

Equities

Equities can also be seen as form of insurance against inflation, as when growth increases, equity prices tend to rise and this rise will tend to insure against rises in inflation. However, since equity prices are perpetual income bearing instruments, the present value of equities is primarily determined by expectations of future growth. As investors well know, those expectations remain highly volatile. Such volatility has resulted in dramatic volatility, especially compared to annual equity returns, as shown below in Figure 4. Not only are equity annual returns much more volatile than annual inflation, annual equity returns have no noticeable positive correlation with annual inflation. Rather, they have a slightly negative correlation; meaning equities are a poor form of insurance against inflation.

Figure 4

As Figure 4 suggests, the rolling five year correlation, between annual inflation and annual equity return has been in decline since the mid 1990’s, and this underscores the conclusion that equities are a poor form of insurance against inflation. We are not alone on this conclusion, as the following quote indicates,

To sum up - if there is any relationship to reveal at all, it appears that inflation and equity returns are actually marginally negatively correlated. This should not be particularly surprising given the poor performance of equity markets during the inflationary 1970's, and subsequent strong performance since inflation has trended lower (Hamilton J., Jones, B., Suvanam, G., Challa, A., (2007), Australian LDI; Liability Driven Investment Has Arrived: Part 1, Deutsche Bank, 18 May 2007, pp.4-5).

One can summarise the advantages and disadvantages of equities, as a form of insurance against inflation as follows:

Advantages

- Participate in growth of the economy, when expectations of growth are strong

Disadvantages

- Volatility of expectations of growth drives equity asset prices, and has very little relationship to CPI, and

- Correlation of returns to inflation is poor and in fact is often negative

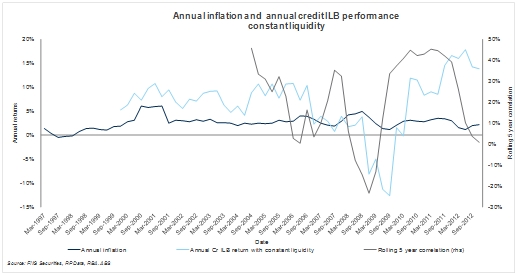

Inflation linked bonds (ILBs)

Credit inflation linked bonds (ILBs) offer a very effective way to insure against inflation, since both the bond principal and interest payments move directly with Australian inflation. In other words, the relationship between inflation and the bond is direct, and causally linked. Typically, issuers have underlying income that is tied to CPI, so they pass that cashflow through to the bondholder, and this means that the ILBs are beneficial; both to the issuer as CPI cashflows are passed through, and to the bondholder as the bondholder secures direct protection from inflation. Rather than being concerned about the correlation to inflation, the ILB investor needs to assess the underlying credit worthiness, or otherwise, of the credit ILB issuer, both at the time of purchase and over the life of the bond.

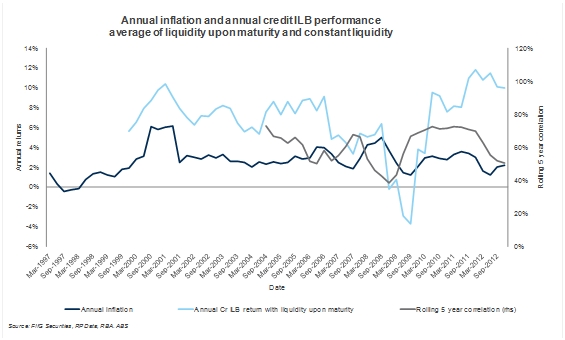

If constant liquidity is not required, then the correlation to inflation tends towards 100%, since the credit ILB provides a constant and direct linkage to inflation. In other words, one can be certain that full insurance against inflation can be achieved, using credit ILBs. This is the appropriate way to view these investments, as they are the long-term anchor of the portfolio, in terms of inflation insurance. We can represent the performance of the credit ILBs, in this way below, in Figure 5 below.

Figure 5

Figure 5

On the other hand, if one needs constant liquidity, then the financial crisis really caused problems for the credit ILBs, due to the purging of securities from institutional investors, during the financial crisis. Here, institutional investors switch into credit ILBs before the GFC, only to switch back out after the GFC, due to a decline from AAA ratings to lower investment grade ratings. This led to large losses, followed by large gains, as what one group of investors found as “trash”, others have found as “treasure”. If daily liquidity is required, then the credit ILB will display volatility to the Australian CPI as the secondary market is constantly re-pricing the following risks, among others, which make the market value of the credit ILB move:

- future expectations for inflation

- future expectations about the short term setting of monetary policy, and

- future expectations about the credit worthiness of the issuer

We can represent the performance of the credit ILBs, in this way below, in Figure 6 below:

Figure 6

Figure 6

In general, the real situation that faces most investors, is somewhere between Figure 5 and 6, which can be represented as the average of these two return streams. FIIG would argue that Figure 5 is most appropriate, as the credit ILB portion of the portfolio should be a long term inflation insurance aspect of the portfolio. Here, the correlation characteristics of the credit ILB remains fairly strong most of the time, and generally is above 20% at most times. We can represent the performance of the credit ILBs, in this way below, in Figure 7 below:

Figure 7

Bringing it all together

As with most forms of longer term expectations, asset price volatility can emerge and can distract the investor from the important role that credit ILBs can play in an investment portfolio. If one ignores this constant volatility, and adopts a strategic, longer-term view, then the benefits are significant, as the volatility of credit ILBs to inflation falls toward zero meaning the credit ILB provides dependable insurance against inflation. If government ILBs are used, then returns to CPI shrink from around 4% to around 2% for semi-governments, or 1% for Commonwealths.

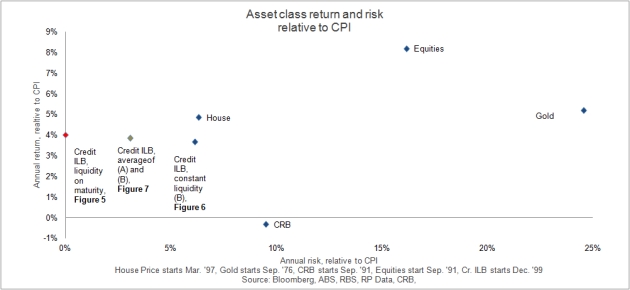

More specifically, assessing all these various forms of insurance together, one can assess the return and risk of each asset class, relative to inflation. In figure 8 below, the vertical axis shows the return over inflation (or real return) from each asset class, while the horizontal axis shows the risk of each asset class, relative to Australian CPI. The higher the risk to CPI, the higher the chance that inflation is not insured against; a lower risk is better, as it means more certainty of insurance against inflation. With regard to credit ILBs, the following three points need emphasising:

- Unlike the charts above, this analysis shows the average return and risk characteristics of all the asset classes, relative to the CPI. Note the credit ILB comes out very well with an annual return of 4% over inflation but a risk measure of 0%, relative to inflation meaning it provides excellent insurance against inflation on a hold-to-maturity basis. A risk of 0 means certainty of inflation insurance. However, this does assume hold to maturity and no need for constant liquidity. Such an approach is considered appropriate as the inflation protection portion of an investor’s portfolio should be permanent and not something that is regularly traded. This point corresponds to Figure 5 above, and is highlighted as the red dot below,

- In contrast, the blue dot, that corresponds to Figure 6 above, shows credit ILBs with constant liquidity, so the possibility of not obtaining CPI increases,

- Finally, the beige dot corresponds to a Figure 7 above, or an average between constant liquidity and liquidity upon maturity.

Figure 8

Hence, the need for credit ILBs persists, if one is serious about insuring against inflation. Moreover, if a low level of liquidity is needed, then ILBs around 4% above inflation come out as clearly the most effective form of insurance against inflation. Here the prospect of achieving a highly effective form of insurance against inflation really depends on the assessment of the issuer, from a credit point of view. Given that FIIG provides detailed credit monitoring of credit ILBs, investors should refer to that research for indications of what the strengths and weaknesses of each credit might be.

Notice how risky all the other asset classes are, relative to inflation, meaning they do not insure one adequately against inflation; they are not “serious” forms of insurance against inflation. Moreover, the use of credit ILBs is attractive at real rates above 3%, and the current pricing available means that inflation insurance is not expensive.

Conclusion

Inflation needs to be taken seriously in the construction of portfolios, especially unexpected inflation. Many possible scenarios support elevated inflation at this time. However, if inflation is taken seriously, then one needs to assess the relative merit of various asset classes, as a source of insuring against inflation. Our analysis has shown that while some forms of inflation insurance are better than others, it remains the case that all the various forms of insurance are far from perfect.

All except one.

Specifically, ILBs provide certainty of inflation insurance, and corporate ILBs at 4% over inflation for solid investment grade companies is inexpensive insurance for investors. As the search for yield intensifies, these forms of insurance will grow more and more expensive, so investors need to consider ILBs sooner, rather than later. Some examples of credit ILBs, along with approximate yields, are as follows:

- Sydney Airport 2030 CIB at 4.35%,

- Sydney Airport 2020 CIB at 3.90%

- NSW Schools 2035 IAB at 3.50%

- ANU IAB at 2.80%

List of References

- Ahmed S. and Cardinale M., 2005,‘Does inflation matter for equity returns?', Journal of Asset Management, 6, 259-73.

- Ang, A. Wei, M. and Bekaert, G., 2008, The Term Structure of Real Rates and Expected Inflation, 63(2) Journal of Finance, 797-849.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2011, Information Paper: Introduction of the 16th Series Australian Consumer Price Index, Australia, September (cat. no. 6470.0).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2005, Information Paper: The Introduction of Hedonic Price Indices for personal Computers, (cat. 6458.0).

- Borio, C. and Filardo, A., 2007, Globalisation and inflation: New cross-country evidence on the global determinants of domestic inflation, BIS Working Papers No 227, Monetary and Economic Department, May 2007

- Binyamini, A. and Razin A., 2007, Flattened Inflation-Output Tradeoff and Enhanced Anti-Inflation Policy: Outcome of Globalization?, NBER Working Paper No. 13280, Issued in July 2007,

- Brynjolfsson, J. B., 2005, Inflation-linked Bonds, Chapter 15 in Fabozzi, F. J. (ed.) 2005. Handbook of Fixed Income Securities. New York, NY: McGraw Hill.

- Campbell, J., and Shiller, R., 1996, A Scorecard for indexed Government Debt, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 5587,

- Campbell, J., Shiller R. J., and Viceira L. M., 2009, Understanding Inflation-Indexed Bond Markets, NBER Working Paper 15014.

- Christensen, J. H. E., Lopez J. A., Rudebusch and G. D., 2010, Inflation Expectations and Risk Premiums in an Arbitrage-Free Model of Nominal and Real Bond Yields, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, (42), 143–178.

- D’Amico, Stefania, Kim, Don, and Wei, Min, 2007, “TIPS from TIPS: The Informational Content of Treasury Inflation-Protected Security Prices,” Finance and Economics Discussion Series (2008), Federal Reserve Board of Governors, Division of Monetary Affairs, BIS Working Paper No. 248.

- Deacon, M., Derry A., and Mirfendereski D., 2004. Inflation-Indexed Securities: Bonds, Swaps, and Other Derivatives, Wiley

- Finlay, R. and Wende S., 2011. Estimating Inflation Expectations with a Limited Number of Inflation-indexed Bonds, RBA Research Discussion Paper 2011-1. Sydney, Australia: Reserve Bank of Australia.

- Gurkaynak, R. S., Sack B., and Wright J. H., 2008, The TIPS Yield Curve and Inflation Compensation. Finance and Economics Discussion Series, Federal Reserve Board Working Paper No. 2008-05, Washington DC: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

- Hugo G., 2012. Co-movement in Inflation, RBA Research Discussion Paper 2012-1. Sydney, Australia: Reserve Bank of Australia.

- Hamilton J., Jones, B., Suvanam, G., Challa, A., 2007, Australian LDI; Liability Driven Investment Has Arrived: Part 1, Deutsche Bank, 18 May 2007.

- Kantor, L., Global Inflation Linked Products: A user’s Guide, May 2012, Barclays Bank.

- Leibowitz, M. L., Sorensen E. H., Arnott R.D., and Hanson, H.N., 1989, A Total Differential Approach to Equity Duration, Financial Analysts Analysts Journal, 45 (5), 30-37, Sep./Oct.

- Norman, D. and Richards A. 2010, Modelling Inflation in Australia, RBA Research Discussion Paper 2010-3. Sydney, Australia, Reserve Bank of Australia.

- Roush J., Dudley W., and Steinberg Ezer M, 2008, The Case for TIPS: An Examination of the Costs and Benefits’, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, no. 353

- Sack, B. 2006, Treasury Saves a Billion on January 2007 TIPS, Monetary Policy Insights, Fixed Income Focus, Macroeconomic Advisors, December 15, 2006.

- ____ 2007, How low is the Inflation Risk Premium?, Inflation-Linked Analytics, Macroeconomic Advisors, May 9, 2007.

- Sack, B. and Elsasser, R., 2004, Treasury Inflation Indexed Debt: A review of the U.S. Experience, FRBNY Economic Policy Review, May.

- Siegel, L.B. and Waring M.B., 2004, TIPS, the Dual Duration, and the Pension Plan, Financial Analysts Journal, (60)5, 52-64, Sep - Oct.

- Stigum, M. and Crescenzi, A., 2007, Stigum’s Money Market, fourth edition. McGraw-Hill,

- Tobin, J., 1963, Essays on Principles of Debt Management, in Commission on Money and Credit, Fiscal and Debt Management Policies, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.:Prentice-Hall, Inc.

- Tristani O., Hordahl P., 2010, Inflation risk premia in the US and the euro area, Bank for International Settlements, Working Paper 235, November.

- White W., 2008, Globalisation and the determinants of domestic inflation, BIS Working Papers No 250, Monetary and Economic Department.