Key points:

- There are three major drivers of a change in investor behaviour toward active management of their fixed interest and other income producing investments: clients demanding income reliability, low deposit rates increasing retirees’ concerns for longevity of their funds and index-tracking results in a rising exposure to increasingly indebted US and EU governments.

- Investors in index-tracking investments may be unwittingly holding more and more US and EU debt.

- A direct investment in corporate bonds enables the investor to negate the rising allocation to US and EU government debt they may have in their fund or ETF investments.

Baby boomers’ transition to retirement will be the dominant feature of our industry for the next decade at least. SMSFs shifted around $34bn from cash to hybrids in July 2012 to June 2013 for example. Similarly, the chase for yield has pushed up the big four banks’ share prices by 35-45% as investors chase yield.

In fact, SMSFs now have around a 53% allocation to the big four banks through the combination of equities, hybrids and term deposits. However unlikely it might seem, a significant downturn in Australian residential property would impact at least the share price of the banks and increase the risk of hybrids being converted to equities. Such a high exposure to a single economic event does not seem to be prudent asset allocation, providing an excellent example of the value of professional advice.

Yet, unlike every other major developed market, Australian investors have less than 1% allocated to bonds directly. Investing directly in bonds gives investors control over the level of risk and return in their portfolio; when to buy and sell bonds and certainty over the timing and level of income they need. A direct investment in corporate bonds enables the investor to negate the rising allocation to US and EU government debt they may have in their fund or ETF investments.

In “the new normal” world there are three major drivers of a change in investor behaviour toward active management of their fixed interest and other income producing investments:

- Clients demanding income reliability

In Australia where there hasn’t been a directly accessible corporate bond market, the search for yield, transparency and control has seen a shift to direct equities, particularly high yielding bank stocks and hybrids. - Low deposit rates increasing retirees’ concerns for the longevity of their funds

While most developed countries’ central banks hold interest rates down to support their economies, individuals dependent upon investment income are being forced to shift into higher yielding assets. - Index-tracking results in a rising exposure to increasingly indebted US and EU Governments

Fixed interest indices are market capitalisation weighted meaning that the more an issuer, such as the US Government, increases its total debt, the greater the share of the index they represent. As these nations seek to rebuild their fragile economies, their asset purchase programs and fiscal support for economies are pushing debt levels into unchartered territory.

Once considered risk-free, post-GFC investors are increasingly wary of investing in these bonds, particularly given the stubbornly low premium for this risk. Those investors in index-tracking investments may be unwittingly holding more and more US and EU debt.

The combination of these points has resulted in traditional index-aware funds returning 3-4% per annum in recent times, and with less income certainty than deposits. This is putting considerable pressure on the financial planning community to seek alternative fixed income strategies.

The rising exposure to US and EU government debt is least understood by clients and provides fertile ground for building a value-adding discussion about portfolio construction.

The need for change - Indices now have much higher government debt

resulting in lower returns and higher duration risk

Equity indices and bond indices are very different in their construction. The more profitable a company is, the greater the proportion of an equity index it is likely to comprise. However, for a company or government to form a greater proportion of a bond index, it needs to be more indebted.

More debt is certainly not always a bad thing as the debt could be used to expand operations and therefore become more profitable. However, the purpose of the debt is not taken into account when creating the index – only the amount of the debt is.

Investing in a global fixed interest index increasingly means investing heavily in some of the world’s most indebted governments. This in itself is not a problem for all investors. But individual or SMSF investors may not be aware of the considerable and building risk associated with index based investment. The risk premium for these governments has barely changed, particularly on a post-fee basis, and given the lack of reliable income, Australian investors are reassessing how they allocate to fixed income.

The “new normal” global economic environment where governments are no longer considered risk-free, has caused advisers and investors to seriously consider whether index investing is still in their best interests. There are two considerations that must be assessed:

- Is an increasing exposure to highly indebted economies such as the US in their best interests?

- Is the resultant increase in duration risk that is exposure to losses in the face of rising interest rates, in their best interests?

Index investors are investing more and more in the high debt US and EU

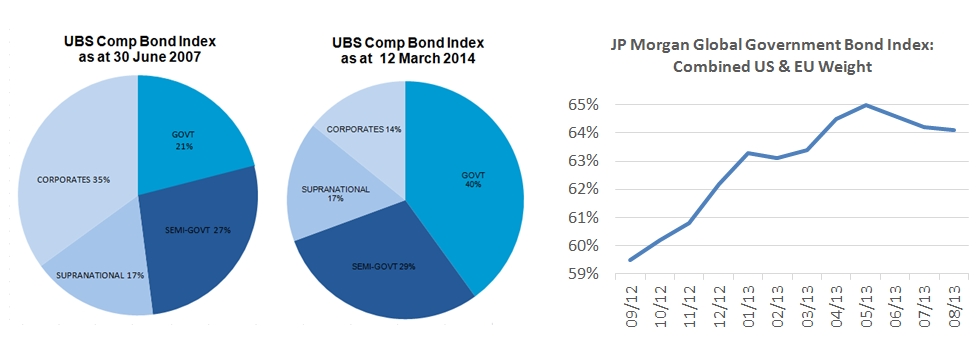

As most bond indices are based on the market capitalisation of the debt on issue, investors in benchmark tracking investments have increasingly been exposed to government debt. Figure 1 below shows the UBS Composite Index and the JP Morgan Global Government Bond Index as examples.

Indices becoming more focussed on Government debt

UBS Composite Index (AUD) and JP Morgan Global Government Bond Index (AUD)

Source: FIIG Securities, UBS and JP Morgan

Figure 1

This increasing debt issuance has meant that government bonds have represented an increasing portion of the major fixed interest indices. It is difficult to argue that this increasing proportion of exposure is in the best interests of many Australian investors.

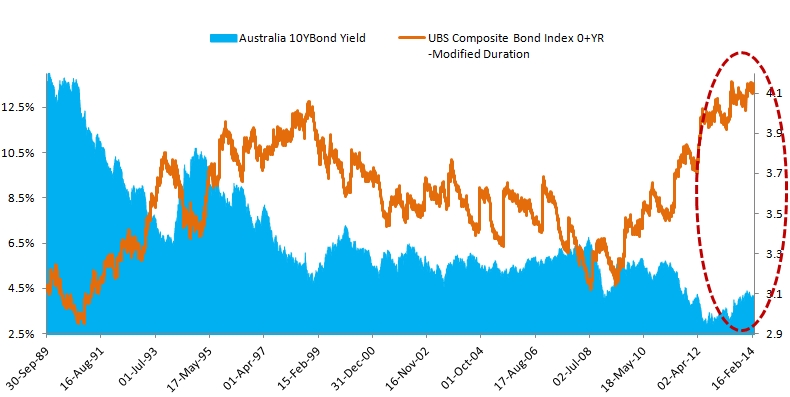

Index investors are increasingly exposed to losses from rising interest rates

Duration risk is a measure of the exposure to rising or falling interest rates. A bond or a fund with high duration risk will lose more value when future interest rate expectations rise, and will gain more value when future interest rate expectations fall.

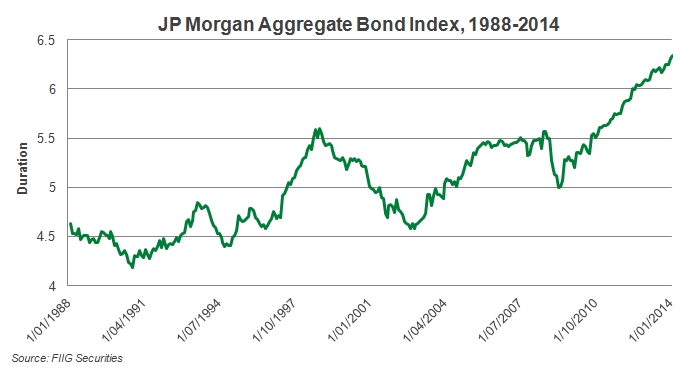

Since the GFC, the steep climb in government debt, typically used to fund economic stimulus programs, has resulted in government debt comprising an increasing proportion of all indices. Because governments tend to issue longer duration debt than corporates, this has the effect of extending the average term of the bonds in the index, that is it increases the duration risk.

As shown in Figure 1, between 2007 and March 2014, government and semi-government debt rose from 48% of the UBS Composite Index to 69%, while corporate debt exposures have fallen from 35% to just 14%. Figure 2 shows the impact that this has had on the duration risk of the Index since the GFC. Duration risk has risen steeply since 2009 and while it has been at these levels before, that was when interest rates were much higher than present.

This is not unique to the UBS Index, and in fact the issue is even more significant for global indices, such as the Barclays Aggregate or the JP Morgan Global Government Index (see Figure 3).

Just as it is difficult to justify Australian investors having greater US and EU government debt exposure, it is also difficult to justify increasing duration risk in this environment. But both of these are outcomes of index tracking investment strategies.

Duration risk at 20 year highs, while interest rates are at 20 year lows

Australian 10 year government bond yield versus UBS Composite Bond Index duration

Source: FIIG Securities, UBS, Bloomberg

Source: FIIG Securities, UBS, Bloomberg

Figure 2

Global Indices show even greater increases in duration risk

JP Morgan Aggregate Bond Index, 1988-2014

Source: FIIG Securities, JP Morgan, Bloomberg

Figure 3

Government bond indices and currency

World government bond indices further distort risk taking by biasing investors towards markets with overvalued currencies. A country’s weight in the index rises as its currency appreciates. Therefore, index-oriented strategies encourage investors to allocate more capital to markets where price risk is high and rising. Conversely, when currencies are undervalued and have the most potential to appreciate, their index weights are at a minimum. From an investment standpoint this is counterintuitive, particularly in the current environment of currency volatility.

Conclusion

For income seeking investors, an allocation to traditional fixed interest index tracking funds is becoming a difficult strategy to put forward due to their low returns and even lower regular income. Worse still, an index-tracking strategy leads investors to hold positions in countries that issue significant debt with questionable compensating return.

In the “new normal”, the US and several other major economies are facing fiscal challenges over the next 10 to 20 years at least. Bond investors need to assess the benefits of investing in fixed interest given their goals and compare the options:

- Where certainty of income, greater control and transparency are the drivers, and not seeking to profit from shorter-term trading opportunities, direct ownership may prevail.

- Where hiring expert bond traders to capitalise on market volatility and macro-economic opportunities are the drivers, active funds management will most likely suit.

- For those investors purely seeking diversification from equity market risk, index funds management will still be the preference.

For individual investors, particularly retirees, who are typically seeking economic benefits such as reliable income without volatility, and psychological benefits such as control and transparency; direct bond portfolios will increasingly meet their needs.