by

Dr Stephen J Nash | Sep 05, 2012

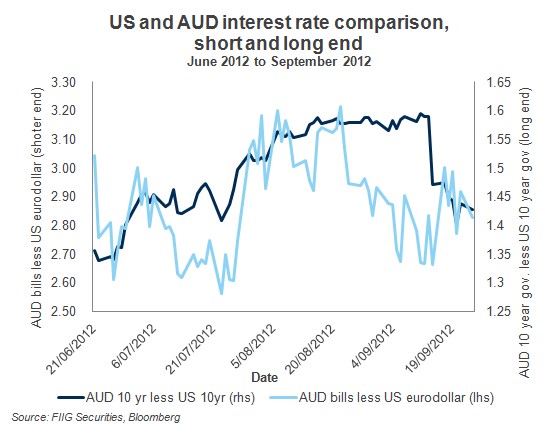

Australia stands out when compared to the rest of the developed world; but we are part of it. Elsewhere, low growth is driving low interest rates, and nominal (fixed rate) returns are often negative from a real-return point of view. While the Australian nominal bond market is pointing towards rates in the developed world, with multi-decade lows in 10 year government yields being apparent, many investors have their heads firmly in the sand; they will not change their “growth” portfolio asset allocations.

A typical Australian portfolio has a 75% equity asset allocation and this simply does not make sense with mounting risks to growth. By not adapting to rapidly changing global dynamics, especially the recent slowing in Australian regional growth, very attractive opportunities are being ignored by Australian investors. One of those opportunities is a 5% real yield (over and above inflation) on investment grade corporate inflation linked bonds (ILBs). Capturing this equity-like return in a senior debt position, remains a rare opportunity for Australian investors. In many ways, therefore, Australia is back to its old ways, of looking inwardly, as if Australia existed in isolation.

US experience is indicative of the situation in the developed world, where low nominal government yields are leading to low real returns, or returns after inflation. In the US ILB market 10 year yields have been negative for some time, and while we do not think it is likely in Australia, the resemblance of Australia to the developed world is increasing, not decreasing. If, as we have seen of late, China experiences lower growth, then growth outlooks in Australia will moderate, and moderate dramatically, leading to a re-pricing of equities and bonds. While the US market has bought the rumour of QE3, the same can be said of the Australian market, which is slowly waking up to the reality of lower regional growth. When we apply the US experience to Australia, we find that corporate ILBs, with around 5% real yield provide the vast bulk of the return provided by equities, without the risk.

US experience

Investors that thought nominal rates would insure against inflation have been disappointed in the US, and these experiences might prove instructive for Australian investors. Figure 1 shows the recent yield history on 10 year US treasuries, and the fairly obvious implication is that they have been very low for a long time.

Figure 1

Figure 2 then shows the nominal yield on US 10 years less the current rate of inflation in the US (1).

Figure 2

Since nominal yields have been so low, the same has been evident for US ILBs, where interest rates have been negative for many months. “Negative?” you might question. Yes, negative real yields have been the case for many months, as shown in Figure 3 below. Negative real rates have been in place for almost a year in the US 10 year ILB market.

Figure 3

However, the negative real yield is not a negative yield in total, as the bond receives a return from the US CPI, which can be shown below, in Figure 4. It is fairly obvious that, as the secondary market real yield on the ILB falls, and negativity increases, the overall return from the ILB falls, that is the ILB yield plus the rate of inflation. Hence, while return is positive, it is only barely positive.

Figure 4

US economic environment

What is driving the low yields in both the nominal US bond market, and the US ILB market, is the perception that growth will be low for a long time. This is not some sort of “bubble”, but a gradual acknowledgement of growth being weaker than previously thought. As Janet Yellen, deputy Vice Chair of the FOMC, recently indicated,

“Forecasters have repeatedly overestimated the strength of the recovery and may still be too optimistic” (2).

This means that investors have gradually accepted lower government bond yields, as inflation and growth are increasingly forecast to be lower for longer, even in the aftermath of the long anticipated quantitative easing; a forecast of which should be given at the end of the week by Chairman Bernanke.

These recent developments serve to highlight the situation where low nominal rates can lead to negative returns on nominal bonds, in a low growth environment.

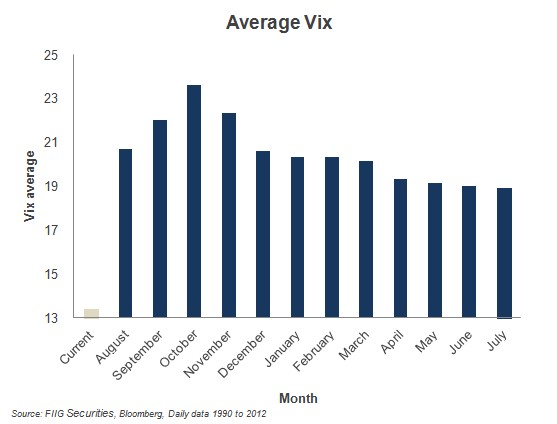

Meanwhile, as US bond prices rise, and yields fall, US equities have already rallied on the promise of an improvement in growth, as created by further quantitative easing known as QE3 (see Figure 5). While we can appreciate the underlying rationale, financial markets have a nasty, yet reliable, habit of “over-doing” things; of driving prices too high, relative to the reality of weak economic growth. While we may be wrong, we think the same is generally the case at present; financial markets have already built in the good news from further QE, and the reality of QE can never live up to these inflated expectations. Hence, the bulk of the rally in equities may well be behind us, we expect volatility to be ongoing.

Figure 5

Application to Australia

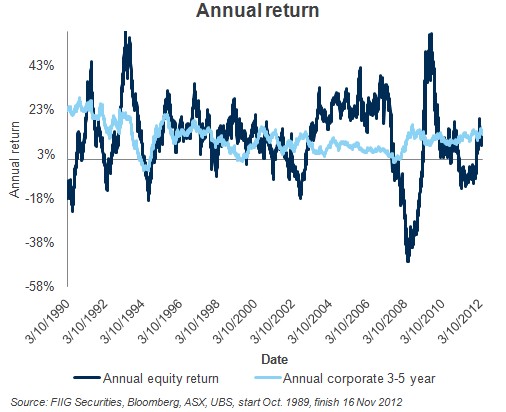

Fortunately, Australian government yields have not fallen to the same extent as they have in the US, yet they are falling, and have touched lows recently around 2.5%. Australia has, to some extent, been immune from the low growth that has been plaguing the rest of the developed world. Yet, the important thing to note, is that things are changing. Australia increasingly resembles the developed world, and the recent collapse in our 10 year nominal yield is only one indication of that resemblance, as shown in Figure 6 below.

Figure 6

Now, add lower growth in China, and the potential for Australia to more closely resemble the investment conditions in the developed world becomes even more apparent. Recently, the RBA has described this undershooting, as a return to more sustainable growth,

Members observed that there were signs that growth in the Chinese economy appeared to be stabilising at a more sustainable pace. Real GDP grew by 1.8 per cent in the June quarter, slightly faster than the March quarter, to be 7.6 per cent higher over the year. Earlier tight monetary conditions, property market restrictions and a normalisation of fiscal policies had led to a slowing in Chinese domestic demand (3).

Despite this growing resemblance, between Australia and the developed world in terms of growth, many small super funds, not to mention institutional investors, still continue to embrace the “growth” asset allocation of 75% equities and 25% bonds.

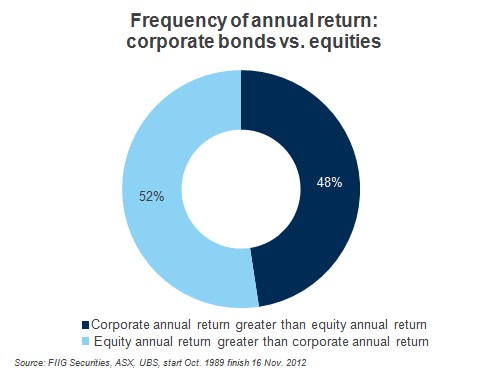

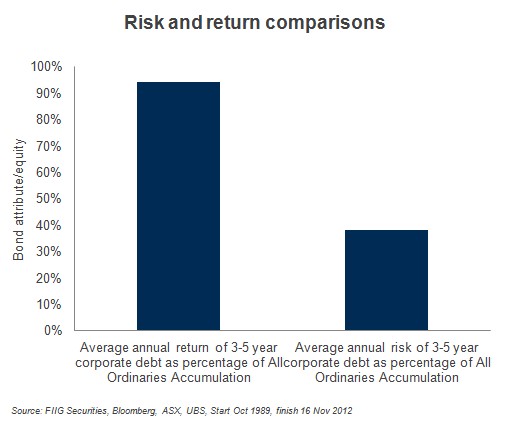

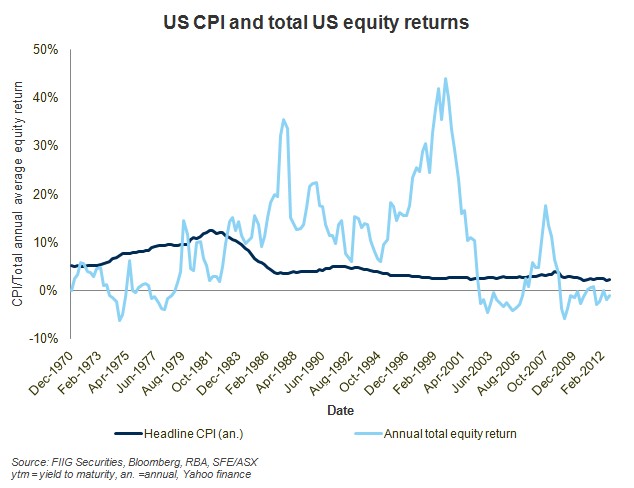

Specifically, if you look at the annual return of Australian equities and take off 5% real, assuming a 3% inflation rate, the average annual return above this is around 2.38%. Yet, in order to obtain this extra return, above 8% (5% real and 3% inflation) you need to incur an annual risk of over 16.27% over 6 times more annual risk is needed to add 2.38% of annual return; an appallingly bad trade-off (4).

Figure 7 shows where the one standard deviation range of return exists, with the light blue line showing the average of 2.38% less 1 standard deviation, and the grey line showing the average return of 2.38% plus one standard deviation. In other words, investors take on a truly enormous risk, in order to generate a return in excess of 5% real (assuming 3% inflation). Whereas a 5% real investment through a senior debt inflation linked bond can generate around 77% of the return from equities, with much lower risk, while the investor retains a senior position in the capital structure.

Figure 7

Conclusion

Looking at global trends is always instructive, and recent calls by many eminent Australians, to reduce the risk in Australian superannuation portfolios, is consistent with global trends and best practice. As we note, the US experience suggests that a low growth environment can punish return, and make negative real yields on government bonds a distinct possibility. While US equity markets have been buying the rumour of QE3 (quantitative easing number 3) for almost two years, the reality of QE will not be enough for the market, and a correction, back towards where valuations might be consistent with slow growth, should materialise after the delivery of QE in September. These trends are beginning to emerge in the Australian market, with the recent dramatic fall in Australian 10 year bond yields. If these trends continue, the current availability of 5% real on an investment grade credit will become a thing of the past, as investors will finally realise the value of these securities. Specifically, corporate ILBs provide the vast bulk of equity returns, for much lower risk.

(1) Assume August 2012 yoy inflation equates that of July 2012.

(2) P.10, Presentation accompanying, “Perspectives on Monetary Policy”, Remarks by Janet L. Yellen, Vice Chair, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, at the Boston Economic Club Dinner, Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, Boston, Massachusetts, June 6, 2012

(3) Minutes of the Monetary Policy Meeting of the Reserve Bank Board, Sydney - 7 August 2012

(4) Risk is derived by looking at the standard deviation of rolling annual return, over the entire period.