by

Elizabeth Moran | Dec 16, 2013

Key points

- A single bank or company can issue bonds that have different risks and thus pay a range of returns as compensation to investors for taking those risks.

- Higher risk bonds should pay higher returns. One of those risks that lead to better returns is known as call risk.

- Of the seven bonds we highlight, the stand-out is the National Capital Instruments (a subsidiary of National Australia Bank) with a yield to call of 5.83 per cent.

A single bank or company can issue bonds that have different risks and thus pay a range of returns as compensation to investors for taking those risks. Bond analysts will assess all the bonds available in the same company to assess which bond has the best return given the risks involved.

The key assessment in bond analysis is if the company will “continue to operate or survive” over the time the bond is issued. If, as an investor you are confident that a company will continue to operate (known as its credit worthiness) it’s worth assessing the higher risk bonds and their specific clauses and current returns to determine if they will be good investments.

For example, when analysing specific companies, an analyst will take comfort in very large companies that have subsidiaries that they can sell, or good access to debt markets (meaning they can easily issue another bond to refinance) or existing shareholders that they could tap for further equity. There are other measures we consider and a high credit rating by Standard and Poor’s or Moody’s may also provide additional reassurance but should not be considered in isolation (credit rating agencies can get ratings wrong).

Higher risk bonds should pay higher returns. One of those risks that lead to better returns is known as call risk. Subordinated bonds usually have longer terms to maturity over senior bonds and as such investors are paid more to hold the bonds. While final maturity dates are longer than senior bonds there is usually a clause which means they can be repaid or “called” earlier at the option of the issuer; often at similar terms to maturity as senior bonds. The interesting thing about call risk is that there is an implied agreement that the issuer of the bond will pay at the “first call”, meaning at the first opportunity and that the term of the bond would then be the similar to the senior bond. So investors are offered higher returns for the chance the term of the subordinated bond would be extended. In Australia, all the major banks have repaid at the first call date, as have many of the regional banks and other financial services companies.

To demonstrate let’s consider some Australian dollar Rabobank securities. The first is a senior bond that matures in October 2015; the bond, if purchased now, would deliver a 3.35 per cent return if held until maturity. Rabobank also have a hybrid (another step lower than a subordinated bond in terms of risk) that has a first call in December 2014, just over a year away. The hybrid has a yield to first call of 4.66 per cent, offering a premium of 1.31 per cent. This hybrid does have another risk if it is not called; it becomes perpetual. That means investors have to sell to recoup their capital. Does the additional return compensate for the additional risk? I think the very short term to call is attractive as is the underlying credit worthiness of Rabobank, but ultimately the decision is up to the investor.

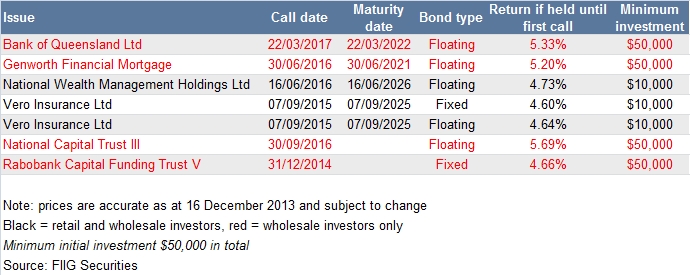

Some of the other over-the-counter subordinated bonds and hybrids available with call options are listed in the table. The stand-out is the National Capital Instruments (a subsidiary of National Australia Bank) with a yield to call of 5.83 per cent.