by

Philip Brown - Head of Research | Dec 11, 2023

Following recent economic data and some comments from officials, it is becoming clear that the US Federal Reserve and the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) are both nearing the peaks of their respective interest rate cycles. However, it is quite possible that the US Fed peaks, and even begins cutting rates much earlier, than the RBA.

Following recent economic data and some comments from officials, it is becoming clear that the US Federal Reserve and the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) are both nearing the peaks of their respective interest rate cycles. However, it is quite possible that the US Fed peaks, and even begins cutting rates much earlier, than the RBA.

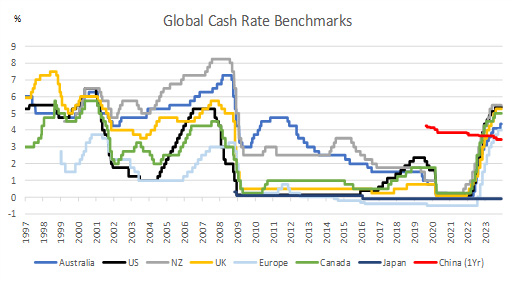

While some measure of global synchronisation is unavoidable thanks to global trade, one of the under-appreciated results of COVID was to create a strong synchronisation for all western economies and western Central banks.

In 2020, all Western Central banks simultaneously cut rates dramatically. Then, once the vaccine allowed normality to resume, there was a near concurrent bout of inflation thanks to celebration spending. That bout of inflation was further exacerbated by a global supply chain problem and a global spike in oil prices driven by the invasion of Ukraine.

Such synchronisation periods have occurred before – for example, during the GFC in 2009 – but they are the exception rather than the norm. As we approach the peak in cash rates, these forces towards global synchronisation of economic cycles are starting to dissipate. A more normal level of synchronisation should take hold.

Australia, although culturally very strongly tied to the United States, is economically far more tied to Asia. 11 out of Australia’s top 13 export destinations are in Asia – with the exceptions being the US at 5th and New Zealand at 8th. Judging by volumes of exports, the US at AUD26.8bn is only very slightly larger than Taiwan at AUD23.9bn.

FIIG expects the current exceptionally high level of global synchronisation to slowly pull apart over 2024. The most likely way this happens is by the US easing back slightly and lowering interest rates while Australia maintains a high cash rate for a longer period, including a possible further hike.

Although all Central Banks began raising rates at nearly the same time, the current Australian cash rate is lower than most other places. That’s partly because of the higher impact of the RBA rate rises through to the economy, but it’s also partly a deliberate policy choice from the RBA.

Many Central Banks around the world have a pure inflation mandate – the only thing their respective governments ask of them is to keep inflation under control. In contrast, the RBA operates under a triple mandate. The RBA is supposed to add to the prosperity and welfare of the Australian people. It seeks to complete this main task but targeting two other outcomes: (1) keeping inflation under control, (2) seeking to create full employment.

While inflation is currently too high, for the first time in a long while, the RBA can credibly say that Australia is at full employment. Nearly everyone who wants a job can have one. This creates something of a dilemma for the RBA – they want to raise rates to lower inflation, but they don’t want to undo the success of their employment mandate that they’ve been seeking for, literally, decades.

So while other Central Banks have hiked rates aggressively and continue to confront inflation directly, the RBA has shown a little more restraint and circumspection. This divergence in policy approach is likely to create divergence in outcome over time.

The most likely result is that other Central Banks around the world will start to cut rates from exceptionally high levels back to more moderate levels, even if there is no clear recession risk in their respective countries. For example, the US probably doesn’t need to leave their rate at the highly restrictive 5.25-5.50% if it becomes clear that their inflation is under control and their economy has clearly peaked.

In Australia, the RBA has deliberately avoided adding those last few rate hikes so it likely won’t have anything like the urgency to deliver rate cuts. Certainly, there will be less pressure to cut rates locally than in other jurisdictions.

For longer-maturity bonds in Australia, the global correlation of interest rates will see longer bond yields fall, even without the RBA. But the shorter-term rates and the fixings on FRNs are likely to stay around current levels into 2024.

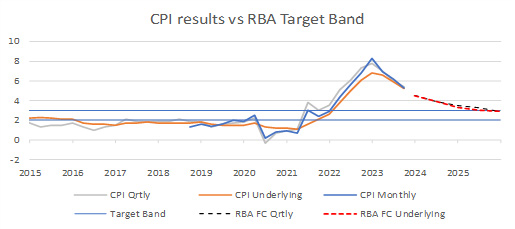

It’s worth noticing that the RBA’s forecast for CPI has inflation dropping back into the target band only in late 2025.

Forecasts are not usually exactly correct of course. But the most recent set from the RBA suggests the RBA’s general understanding of how the economy will develop does not require a rate cut until late 2025. With that said, however, the recent survey data on prices and the monthly CPI for October were both lower than anticipated, as was the GDP result. If these trends continue, then the RBA will revise their forecasts for CPI lower, which in turn would allow them to cut rates earlier – but it means the rate cuts will be earlier than late 2025. It doesn’t necessarily mean the rate cuts should be expected soon.

For more information on Corporate Bonds

Talk to us

Call us on 1800 01 01 81

...with offices based in Sydney, Brisbane, Melbourne and Perth